H&R Block has had a rough time lately. First it was the refund loan scandal a few years ago whereby Block charged usurious effective interest rates to clients who wanted their refund immediately, rather than six weeks later when the IRS got around to sending them. Block weathered that one ok by fixing the program and eventually rebounded to post record earnings.

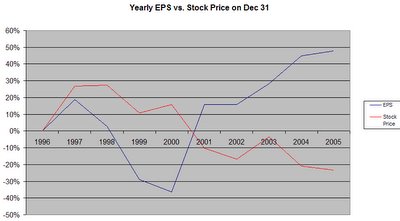

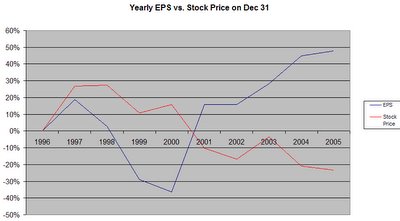

But things turned south quickly thereafter, and the company began an effort to transform itself into more than just a tax preparer by originating a few mortgages. In the near term, this appears to have hurt its profitability. Indeed, sales were up considerably in FY2005, but income was down sharply. All indications for 2006 seem to be similar, and will be hurt even more by the legal costs the company now has to deal with.

Another of its areas of expansion has been investments, which seems to have gotten the company into yet another pickle. Today Block is defending itself against a $250 million Eliot Spitzer lawsuit for yet another of its take-advantage-of-the-idiots practices – the “Express IRA.” It seems this was a deal in which clients were encouraged use their refund check to open an IRA held by Block. Sounds good to me, but the always-politically driven New York Attorney General took exception to this practice since the fees Block charged often amounted to more than the account was earning.

There is little debate that Spitzer lawsuits usually have more to do with getting voters' attention in preparation for a gubernatorial bid than they do with trying to clean up business. A case can be made that he has resolved a lot of ugly problems, but more often than not a Spitzer lawsuit is nothing more than extortion. AIG worked out this way exactly. Nobody outside the insurance industry really understood what the heck was wrong with the transactions in question, so it was easy to paint Hank Greenberg as the bad guy and Eliot Spitzer as the hero. Needless to say, it is not certain that this new lawsuit has much merit.

So now we are dealing with the Spitzer lawsuit, several copycat class action suits and news that Block will have to restate its financials because it inaccurately calculated

its own tax liability. Yikes. I can’t imagine Wall Street rewarding this company anytime soon.

None of this, though, changes the fact that H&R Block is without question the strongest franchise in the industry. Nearest rival Jackson Hewitt doesn’t even come close - compare Block’s 2005 revenue of $4.2 billion with the $233 million of Jackson Hewitt. The company produces boatloads of free cash flow and the potential threat of tax software has never really materialized. That is, the company is not going anywhere, but its stock price has been falling steadily for a few months.

So let’s watch this one and see if all this negative publicity doesn’t drive down the share price a little further. At its current price of around $21/share, the company’s 2005 free cash flow (owner earnings) would need to grow at less than 2% on average indefinitely in order for the present value of that free cash flow to equal the current stock price (assuming k=10%).

I remember at the 2002 annual meeting, Mr. Buffett mentioned a good investment idea was to buy shares of companies whose price was beaten down by asbestos litigation. Had I listened to him I might have bought Halliburton (yes, I realize there is a lot more to that company's stock price than an asbestos settlement but my point is made). It will be interesting to see if he adds to Berkshire's H&R Block position. Given that H&R Block is indeed in pretty bad shape right now and its near term prospects uncertain, I’m not to anxious to buy at $21, but should the stock continue to fall it may prove to be an ideal value purchase.

As of now, I do not own any shares of H&R Block.